Islam in the Malay-Indonesian World Can Serve as An Example for Diversity, Tolerance and Democracy

A number of global events have put a spotlight on Muslim countries such as Afghanistan, Sudan, Nigeria and the Middle East, particularly after the Arab Spring of 2011. These Muslim countries are plagued by a variety of problems and misery. When we view their situation, we might ask: ‘Is there a Muslim country that can potentially become a reference or a role model for the Muslim world?’

Dr. Kamarudin Amin, director general of Islamic Studies at the Religious Affairs Ministry, suggests that the answer is Indonesia. This is strengthened by the fact that Indonesia has a very solid social infrastructure, such as the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Muhammadiyah, and other moderate mass-based organisations. These organisations, the largest Muslim groupings in the world, are reknown for promoting an Islam that emphasises ‘rahmatan lil alamin’ or ‘blessings for all the worlds’ for decades (The Jakarta Post, 21 December, 2015).

Therefore, it is not easy for global radicalism and extremism to become dominant in Indonesia as they will have to contend with various peace-loving and tolerant religious leaders and members of these organisations. This is a distinctive strength of Indonesia’s social infrastructure that many other Muslim countries have yet to develop within its civil society. Another edge that Indonesia has as the most populous Muslim country in the world is its democratic institutions. Indonesia is the third largest democratic country in the world and has shown comparative success in blending Islam and democracy since the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998.

This argument is echoed by the American anthropologist, Dr. James B. Hoesterey of Emory University, who had conducted extensive research in Indonesia (Republika, 18 October, 2015). He suggests that the global community take a deeper look into the manifestations of Islam in Indonesia, which may differ from how Islam is being represented in other countries, such as Saudi Arabia. He notes that Indonesia is a good example to learn from.

Indonesia has extraordinary potential and can be a hope for a global reference point with respect to a Muslim democratic nation. This is not impossible, given that Indonesia has long been recognised as a relatively moderate Muslim country where its mainstream views on Islam have succeeded in fending off foreign radical ideas that began to creep in after the downfall of the New Order regime. Till today, radical and extremist groups remain as fringe groups within the vast majority of about 250 million Muslims in the country.

The Nahdlatul Ulama, Muhammadiyah and other moderate Islamic mass-based organisations has exercised their critical and important role in maintaining, nurturing and protecting Indonesian Islam from influence by radical or extremist ideology. Indonesian Islam is also well-known for its democratic, tolerant and moderate form. It is also rooted in the indigenous tradition and local wisdom of the Indonesian people, and appreciative of the diversity of cultures, ethnicity and religions. It is true that sporadic communal conflicts over religious differences did occur in Indonesia, but they were few and far between, given that Indonesia is a hugely diverse country in terms of demography, geography, religion and culture.

In 2015, amidst the global anxiety against the threat of ISIS, the moderate face of Indonesian Islam became a further topic of discussion among religious leaders, observers, diplomats and community leaders at the headquarters of the United Nations in New York. Discussions on ‘Islam Nusantara’ (Islam of the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago) were initiated by the Permanent Representative of the Republic of Indonesia to the United Nations, the Nusantara Foundation and Dompet Dhuafa Foundation. Islam Nusantara serves as an example for the countries of the world in demonstrating the diversity, tolerance and democratic values within Islam (Republika, 30 July, 2015).

The term ‘Islam Nusantara’ was first promoted widely by the Nahdlatul Ulama, the largest muslim organisation in the world that has more than 80 million members. It is one expression of Indonesian Islam, in addition to the concept of ‘Islam Berkemajuan’ (Progresive Islam), which was promoted by another significant movement, the Muhammadiyah. It is interesting to note that efforts to define and promote Indonesian Islam were highlighted simultaneously in both, Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah congresses, around the same period in 2015.

The congress (muktamar) of Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah had garnered widespread attention from the public, including foreign observers and researchers, partly because both were Indonesia’s most important civil society organisations whose members and sympathisers have participated in the shaping of moderate values and sensibilities for Indonesian Muslims over the decades. Despite the fact that the two adopted different types of religious expressions and practices, notably in daily rituals, they have shared common concerns about the presence of Islam in public life. For example, Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama have rigorously supported democracy, social justice and welfare in Indonesian society through various religiously-inspired social, economic and educational programs throughout the country (The Jakarta Post, 7 August, 2015).

But more importantly, they are in the midst of debating the phenomenon of ‘Arabisation’. In Indonesian Islam discourse, ‘Arabisation’ is understood as a phenomenon that displaces local cultures, traditions and wisdom through the adoption of a puritanical form of Islam as practiced in places like Saudi Arabia. Hence, the emergence of ‘Islam Nusantara’ as a concept, is an attempt to address the backsliding of Muslims from the fundamental characteristic of Islam in Indonesia: tolerance of diversity and openness to difference.

Indeed, there are among Muslim scholars and intellectuals, those who think that Islam is only one entity and the same for every region and nation. Professor Fouad Abdel-Moneem, dean for International Students Dirasah Islamiyah Al-Azhar University, Cairo, in a pre-Nahdlatul Ulama congress seminar, proclaimed that Islam is only one, and that ‘Islam Nusantara’, ‘Arab Islam’ or ‘Egyptian Islam’ does not exist. But leading Indonesian intellectual and former rector of Syarif Hidyatullah State Islamic University in Jakarta, Professor Azyumardi Azra, said that Professor Fouad’s view is more based on an idealistic framework (Republika, 4 July, 2015).

This view does not take into consideration the historical-empirical reality of Islam throughout history in various regions which manifest diverse social realities, cultures, and politics. Referring to the historical-empirical reality of Islam, the general chairman of Nahdlatul Ulama, Kiai Haji Said Aqil Siradj emphasises that the concept of ‘Islam Nusantara’ describes Indonesian Muslims who blend local cultures and wisdom with the universal teachings of Islam.

In other words, local community practices (known as ‘urf in Islamic legal tradition) are not shunned or displaced as long as they do not run against the universal values and teachings of Islam. This process – of blending local cultures with universal aspects of Islam – has been on-going in the Malay-Indonesian world since the first coming of Islam to this region. The late Muslim scholar and fourth president of the Republic of Indonesia, Abdurrahman Wahid, calls this process as ‘pribumisasi Islam’ or ‘indigenisation of Islam’.

Muslims in Indonesia are closely associated with the cultures of where they live and this is what forms the foundation of the concept of ‘Islam Nusantara’ that differentiates Indonesian Muslims from their counterparts elsewhere, such as those in the Middle East. Hence, we need not worry that ‘Islam Nusantara’ will become a new sect because, as Professor Azra asserts, the ulama will always be there as a reference point to ensure that ‘Islam Nusantara’ will remain authentically Islamic and a subset of the greater Islamic tradition. Hence, ‘Islam Nusantara’ is neither a new school of thought nor sect, but rather a worldview of Muslims in this region that is at ease with the long-held and multifarious cultures of the Malay-Indonesian world.

But as a concept, ‘Islam Nusantara’ must move beyond the confines of Indonesia. This term should embrace the maritime continent of the Malay-Indonesian world, covering not only the area that is now called Indonesia, but also the experiences of Muslims in Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, southern Thailand (Pattani), southern Philippines (Moro/Mindanao) and also the Cham region of Cambodia. Hence, ‘Islam Nusantara’ is equivalent to the term ‘South-east Asian Islam’. Academically, the last term is often used inter-changeably with ‘Malay-Indonesian Islam’.

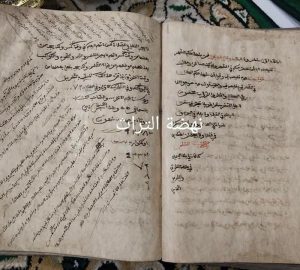

As a normative doctrinal position, Professor Azra said that ‘Islam Nusantara’ embraces the same theology of the Ahlus-Sunnah wal-Jama’ah (Sunni) as other parts of the Islamic world, and as agreed by the authoritative jumhur ulama (majority of ulama). However, the distinctiveness of ‘Islam Nusantara’ can be seen from grounding of these teachings within local context. This was done through a well-established network of local jawi (Malay-Indonesian) ulama connected to the ulama network based in Mecca and Medina – particularly since the 17th century.

Scholars like Syekh Nuruddin ar-Raniri (d. 1658), Syekh Abdurrauf al-Singkili (d. 1693), Syekh Muhammad Yusuf al-Maqassari (d. 1699), Syekh Arsyad Al-Banjari (d. 1812), Syekh Nawawi Al-Bantany (d. 1897) and Syekh Yasin Al-Padangi (d. 1990), had ensured the orthodoxy of ‘Islam Nusantara’ even as they ground them in local cultures and traditions.

As a comparison, the orthodoxy of ‘Islam Nusantara’ is different from the orthodoxy of Islam as practiced dominantly in Saudi Arabia. The latter contains the elements of a literal understanding and interpretation as found in the theology of Salafi-Wahhabism that seeks a ‘puritanical’ version of Islam. Within Sunni orthodoxy – as found in ‘Islam Nusantara’ – Sufism or ‘mystical Islam’ is not shunned and cultural practices such as the maulid (celebration of Prophet Muhammad’s birthday) is not prohibited. In addition, Sunni orthodoxy accepts Shi’ism – particularly of the Ithna ‘Ashariyyah (Twelver Shi’ism – the dominant and majority form of Shi’ism) and the Ja’afari school of thought – as a part of Islam. This runs contrary to the Salafi-Wahhabi Islam that is largely against Sufism and Shi’ism.

Therefore, when talking about ‘Islam Nusantara’, as Professor Azra argues, we can also be sure that the form of Islam as practiced by the Indonesians has been tolerant of diversity. In fact, this is the form of traditional Islam that Muslims all over the world had been accustomed to. Its is an Islam that promotes peaceful co-existence and acceptance of the diversity within Islam itself, as well as across the different religious communities.

In fact, this is the form of Islam that draws its inspiration from the life of Prophet Muhammad himself and the teachings of early Muslim scholars. Perhaps, this is what we need to counter the growing threat of Muslim extremism and fanaticism that seek to obliterate diversity and sow conflict in society. ‘Islam Nusantara’ can make a contribution in this time of great anxiety due to the violence perpetrated by a small minority claiming to speak in the name of God.